Blog

A school mock election with a difference!

Charlie Pearson

Head of History and Politics at Bristol Grammar School

Read the blog

Rishi Sunak’s 22nd May snap election announcement, robbing me of my chance to plan the Bristol Grammar School mock election (which would have included the presence of the year 11s and 13s) in meticulous detail over the summer, was a shock but nevertheless a much-needed spur to action!

Alongside giving the student body the chance to enjoy themselves both participating in and watching campaigning, canvassing and hustings etc, I also think the calling of a general election is a wonderful opportunity for them actually to scrutinise the weirdly fascinating (and for some highly questionable) process by which we choose our governments in the UK. Standard school mock elections (many of which I have organised) do not really do this justice. They run the election as a single constituency, or presidential, election in which one candidate simply outmanoeuvres the others by attracting the most votes through being more charismatic/popular/attached to the “correct” party etc. This really misses the central point of a general election – it is not about votes, it is about parliamentary seats. Votes, for anyone in the know, do not in any sensible way correlate to seats won by a party.

And this is something we hope really to get across in our mock election this year, which will involve the use of, not one, but two voting systems and not two, but three, methods of translating the number of votes won by each party into seats:

Electoral System #1 – Tutor Group “Constituency” Vote

This one is all in the title essentially. All students (and their tutors) will vote in one of 60 tutor groups (with a Microsoft Forms-based “postal vote” for Upper 6th and Year 11 groups). The names on the ballot will be the leader of each party-based campaign across the school (Conservative, Labour, Lib Dem, Green and Reform UK) and a cross will be put next to the candidate preferred by each tutee.

Electoral System #2 – House-based “Regional” Party Vote:

On this second ballot paper will be the list of parties. Students will vote in one of the school’s six houses, each of which will return 8 further seats (i.e. 48 to add to the original 60 tutor group seats). The purpose of this, as shall be seen, will be to “correct” the biases of the first-past-the-post system (as used in UK general elections) by weighting the house count in favour of the candidates who have been left underrepresented in the tutor group vote.

Count #1 – First-Past-The-Post, simple:

This will be a simple first-past-the-post count based on the number of constituencies won by each party. This might result in one party gaining more than 30 of the tutor group constituencies and their leader being in a position where the party leader can ask the Head if they are able to form a Government OR, perhaps more likely, in two or more party leaders having to negotiate a policy platform on which to ask to form a government. Either way, the link between “getting across the line” in enough constituencies and having the right to form the government will be more firmly established in students’ heads.

Count #2 – First-Past-The-Post, “weighted”:

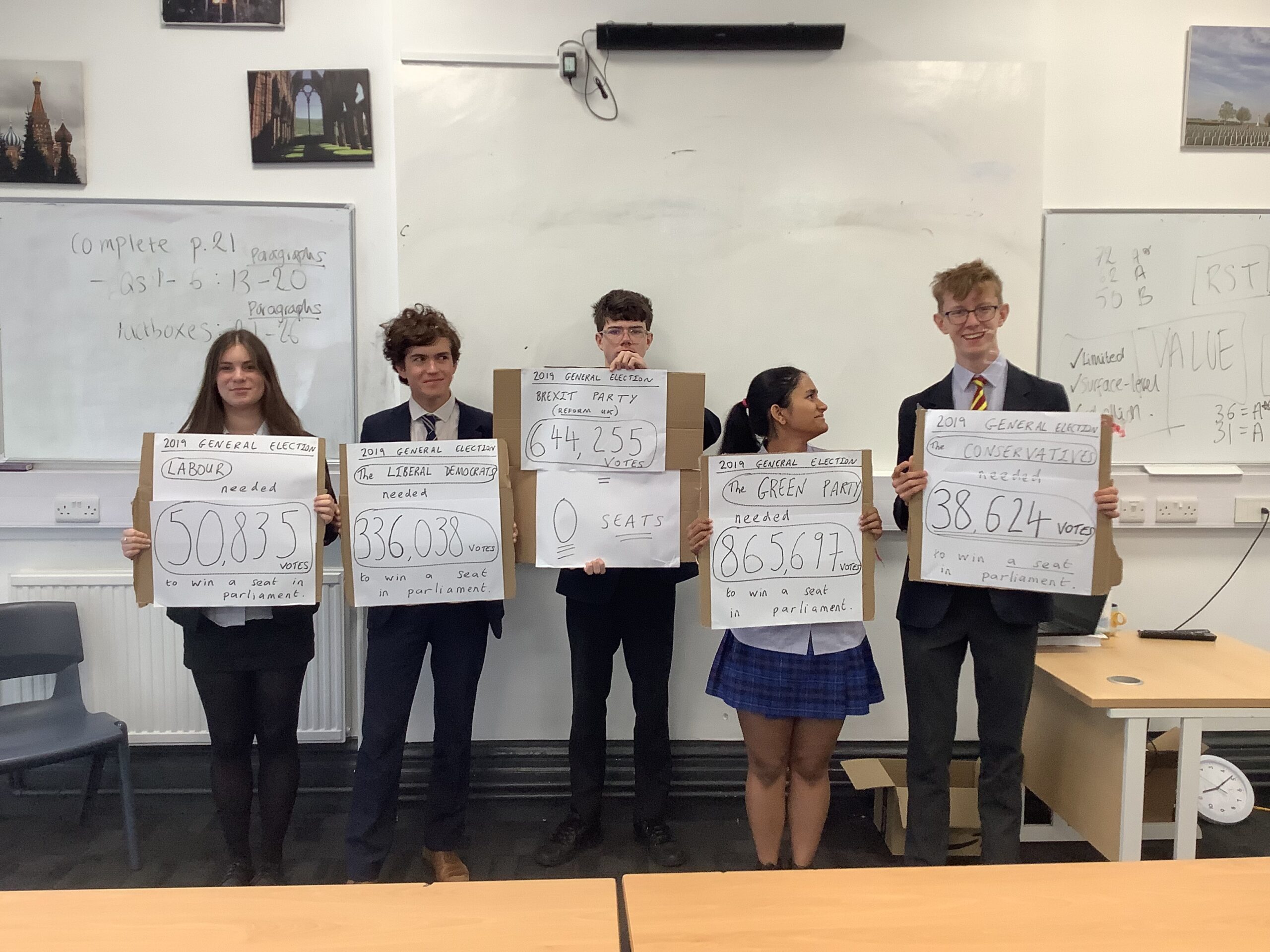

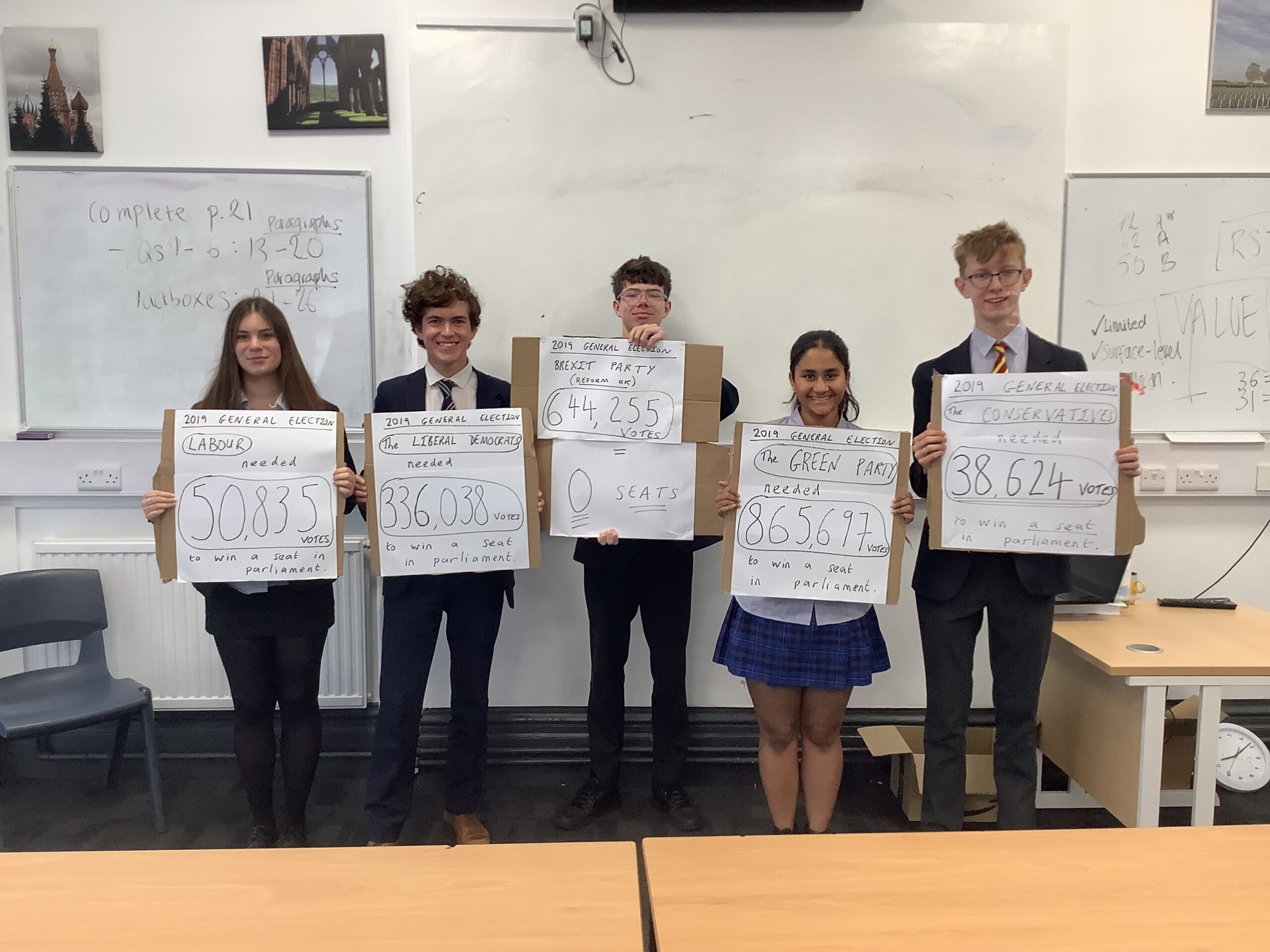

Of course, without the cultural/historical context of the UK’s history of being a (traditionally) two-party democracy with Conservative and Labour-dominated funding, campaigning and tactical voting, the school seat share will most likely lack some of the more eye-wateringly disproportionate elements of your average general election. For this reason the 60 seats counted above using first-past-the-post will be recalculated according to the percentage seats:votes ratio at the 2019 general election. For each party this will involve multiplying the percentage of the 60 seats they actually receive in the following way: Conservatives (56.2% seats:43.6% votes) – × 1.29; Labour (31.1%:32.1%) – × 0.97; Lib Dems (1.7%:11.5%) – × 0.15; Greens (0.2%:2.7%) – × 0.07; Reform, as successor to the Brexit Party, (0%:2.0%) – × 0 (which, of course, means 0 seats whatever percentage of the vote they get!).

Although this might not end up filling all 60 seats, the glaring mathematical injustice of this will not be lost on students!

Count #3 – Additional Member System (AMS):

Using the d’Hondt formula (number of house-based “regional” votes ÷ number of seats already won + 1) on a round-by-round basis to calculate the remaining 48 house seats to be added to the 60 already allotted in Count #1. This should bring the number of the 108 overall seats allotted to each party much more closely in line with the number of votes they have actually achieved – hopefully a valuable insight into the possibilities of proportional representational (PR) voting and the systems actually used to elect the legislatures of countries like Germany, New Zealand, Scotland and Wales.

I hope the pupils will find the mock election fun and engaging and will takeaway key learnings in this democratic experiment. For me, how we elect our governments and politicians is something which is not thought about enough. As I concluded in a recent assembly linking the 80th anniversary commemoration of D-day to our mock election: the veterans fought to rid Europe of unthinking dictatorship; we owe to them now to use our freedoms to scrutinise and challenge unthinking democracy.

BGS mock general election experiment – results:

Just like the real general election held a week later, the BGS mock election results yielded a clear leader, but no party with a majority of the vote share. Unlike the national election though, this did not translate into a majority of seats being held by the winning party under either of the voting systems used (although it emphatically did when accounting for the historical/cultural biases of UK general elections). The Additional Member System (AMS), however, did give all five parties a seat share that was much more representative of their vote share in comparison to First-Past-The-Post (FPTP), particularly in the case of the most and least successful parties.

First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) Results:

Under first-past-the-post, the Green Party was the clear leader, winning 27 of the 60 available tutor group “constituency” seats. They were awarded the usual “winners bonus” you would expect under FPTP, receiving 45.0% of the seats based on 33.0% of the vote. Accordingly the least well supported party, the Conservatives, were rather brutally underrepresented winning only 1 seat (1.7%) based on 7.5% of the vote. The three other parties received very similar vote shares (Labour – 20.7%; Lib Dem – 19.5%; Reform – 19.2%) with Labour overrepresented with 14 seats (23.3%) and the other two underrepresented with 10 seats for the Lib Dems (16.7%) and 8 seats for Reform (13.3%). Although some political wrangling would be required to decide which government should be formed off the back of this, one viable option would be a Green/Lib Dem coalition (37 of the 60 seats) with the Labour as the main opposition.

TUTOR GROUP “CONSTITUENCY VOTE” UNDER FIRST-PAST-THE POST

| Party (leader) | Votes (total – 769) | Vote % | SEATS | Seat % |

| Green (Candidate A) | 254 | 33.0% | 27 | 45.0% |

| Labour (Candidate B) | 159 | 20.7% | 14 | 23.3% |

| Liberal Democrat (Candidate C) | 150 | 19.5% | 10 | 16.7% |

| Reform UK (Candidate D) | 148 | 19.2% | 8 | 13.3% |

| Conservative (Candidate E) | 58 | 7.5% | 1 | 1.7% |

31 seats needed for a majority. Probable result – Green/Lib Dem coalition with Candidate A as PM and Candidate C as Deputy PM and Candidate B as leader of the Labour Opposition.

—————————————————————————————————————-

First-Past-The-Post Results adjusted for historical/cultural biases of UK general elections:

Students were given a clear indication of the strength of the historical and cultural biases of the first-past-the-post system when the seat count was recalculated according to how many votes it took for each party to win a seat in the 2019 general election. The result (using exactly the same voting figures for the count above) yielded the following seat count: Labour – 35 seats; Conservatives – 16 seats; Lib Dems – 5 seats; Greens – 4 seats; Reform – 0 seats. This, of course, would be a comfortable parliamentary majority for Labour despite finishing a distant second in the popular vote, with the otherwise last-placed Conservatives forming the main opposition.

TUTOR GROUP “CONSTITUENCY VOTE” but scaled to reflect the number of votes needed by each party to win a seat in the 2019 General Election

| Party (leader) | % votes received | Multiplier based on 2019 General Election | 2019 GE-scaled seats in BGS mock election |

| Labour (Candidate B) | 20.7% | x 0.97 | 35 |

| Conservative (Candidate E) | 7.5% | x 1.29 | 16 |

| Liberal Democrat (Candidate C) | 19.5% | x 0.15 | 5 |

| Green Party (Candidate A) | 33.0% | x 0.07 | 4 |

| Reform UK (Candidate D) | 19.2% | x 0.00 | 0 |

Labour Majority government with Candidate B as PM and Candidate E as leader of the Conservative Opposition

—————————————————————————————————————-

Additional Member System (AMS) Results:

Finally, the seats were calculated according to the part majoritarian/part proportional Additional Member System (AMS). This involved combining the tutor group/constituency vote with a second ballot cast by all students and staff in a house-based/regional round. The 48 house seats (8 for each of the 6 houses) were calculated on a round-by-round basis using the d’Hondt formula (house votes ÷ number of seats already won + 1) with the number of seats already won including the seats already won by each party within the house in question in the tutor group/constituency round. This, of course, served to penalise the parties that had been overrepresented in the tutor group round.

As a result of this recalculation all parties ended up receiving a more representative share of the seats. The Greens, while still the front runner with 40 out of the 108 combined tutor group and house seats, was less overrepresented having won 37.0% of the seats based on 33.9% of the combined vote share. The Conservatives, while still an underrepresented backmarker, saw their position improve with 5 combined seats making 4.6% of the combined seats based on 7.5% of the vote share. Labour’s representation under AMS was almost perfectly proportional with their 21 seats constituting 19.4% seats based on 19.9% of the votes. The Lib Dems were the big winners in the house-based round increasing their seats from 10 to 25 ending up with a seat share of 23.1% based on 20.5% of the popular vote while Reform’s underrepresentation was at least ameliorated, their 17 combined seats giving them 15.7% of the seats based on an 18.2% vote share. Under this voting system, the most likely government to emerge would instead be a Green/Labour coalition (their combined 61 seats getting them above the required 55/108 for a majority) with the Lib Dems as the main opposition.

COMBINED TUTOR GROUP + HOUSE VOTE UNDER THE ADDITIONAL MEMBER SYSTEM (AMS)

| Party (leader) | Combined Tutor Group and House vote (total – 1,501) | Combined % of votes | Combined tutor group and house seats (total – 108) | Combined tutor and house seats % |

| Green (Candidate A) | 509 | 33.9% | 40 (27 + 13) | 37.0% (FPTP – 45.0%) |

| Liberal Democrats (Candidate C) | 308 | 20.5% | 25 (10+ 15) | 23.1% (FPTP – 16.7%) |

| Labour (Candidate B) | 299 | 19.9% | 21 (14 + 7) | 19.4% (FPTP – 23.3%) |

| Reform UK (Candidate D) | 273 | 18.2% | 17 (8 + 9) | 15.7% (FPTP – 13.3%) |

| Conservative (Candidate E) | 112 | 7.5% | 5 (1+4) | 4.6% (FPTP – 1.7%) |

55 seats needed for a majority. Probable result – Green/Labour coalition with Candidate A as PM, Candidate B as Deputy PM and Candidate C as leader of the Lib Dem Opposition.

———————————————————————————————————————

Suffice to say, according to this research carried out at BGS, the way we elect our representative governments really does make a difference. It might perhaps pay for attention to be refocused on the merits of Westminster system which has held sway, largely unquestioned, for centuries.