Blog

A trip to Oz: From Aria to RSL

Dr Simon Hyde

HMC General Secretary

Read the blog

This summer Kate Howell, HMC’s Director of Education, and I were fortunate to visit several of our members in Australia. Headteachers from Australia were amongst the first to join HMC’s international division when it was established in 1921 and four of them went on to found the Headmasters’ Conference of the Independent Schools of Australia in 1931. This body merged in 1985 with the association for headmistresses to form AHISA (Association of Heads of Independent Schools in Australia) and I am very grateful to Dr Chris Duncan, the association’s current CEO, for welcoming Kate Howell and I this summer and for suggesting the title of this piece.

For me, the trip began in Melbourne, capital of the state of Victoria. Given the recent and unheralded introduction of a payroll tax on Victoria’s independent schools, it seemed the obvious place to start. That and the fact that I was able to meet up with a pupil from my first ever history class, who has been living in Melbourne for the last twenty years and making use of its independent schools for his three children.

HMC General Secretary with staff at AHISA in Canberra (above) and AHISA Branch Meeting (below)

Whilst the payroll tax in Victoria was an unwelcome pressure on schools’ budgets (not least because there had been no forewarning) non-government schools still receive state and federal funds towards the cost of education. In Australia, the government believes it should support the education of all children and not just those in state-run schools. The children of wealthier Australians who choose independent education are entitled to some support, though it is distributed based on socio-economic need. A school with very wealthy parents (generally charging high fees) will receive less money than a school whose parental incomes are less. This used to be apportioned by postcode, but now the government uses individual tax data to make a more accurate calculation.

The payroll tax has added significant costs to Victoria’s private schools, though a concession was won by the influential Catholic schools’ lobby to apply the tax (4.85%) only to those schools whose per pupil income was greater than $15k (c. £7,500). In Australia there is a much greater diversity of price point for the independent sector. Government schools (state schools) educate about 64% of school-age children with funding mainly from the state authorities, though with some support from the federal government. About 20% of children attend Catholic schools which can charge fees in addition to financial support that largely comes from the federal government. The remaining 16% of children go to private schools (often Anglican or Presbyterian) though fees vary widely. A high-fee day school can charge over $40k a year. A low-fee school might charge as little as $6 or about £3k.

Another distinction between education in Australia and the UK concerns the employment status of headteachers and some senior leaders. Fixed-term contracts are the norm, with renegotiation and possible extension after five years. Whilst this does not prevent some heads enjoying long tenure, it nevertheless introduces a degree of uncertainty that may not always be conducive to a head’s wellbeing, though the current author could not discern any negative impact on the quality of the schools visited.

Whilst some UK schools, especially in London and with great names, are accustomed to media interest, the situation in Australia appeared to be of a wholly different scale (at least as far as the big cities is concerned). The hostile press environment can make being an independent school headteacher a risky business. School boards or Councils can be quixotic and I lost count of the number of heads who had departed at short notice or had only escaped a board coup with some astute political manoeuvring.

In Melbourne I visited Trinity Grammar School, an impressive boys’ day school led by an equally impressive Head, Adrian Farrer. The school was the subject of some controversy a few years ago when the Council determined to sack a popular Deputy Head, who cut a student’s hair before a school photo. The resulting crisis led to the departure of the chair, board members and then the Head in an extraordinary combination of student, former student and parent action. It is probably fair to say that the experience of that time still runs deep in the psyche of the school, and it is testimony to Adrian’s diplomacy and skill that he has steadied the ship so successfully.

Melbourne (above) and Dr Simon Hyde with Adrian Farrer at Trinity Grammar School (below)

The press’s pre-occupation with high-fee independent schools is especially vehement in Sydney. The more prestigious the school, the higher the value as ‘click bait’. And this is perhaps one potential downside of public funding. Scrutiny of independent schools by the media and, on occasion, by the state and federal authorities can be forensic whenever there is the chance that public funds have been used to support any activity that does not find favour. The fact that the public funds will have been entirely expended many times over on education does not diminish the clamour. Heads’ expenses, improvements to school accommodation or even architectural preferences can all be subject to the disapproval of the fourth estate.

Despite this, most of the senior leaders I spoke with were remarkably sanguine about the durability of state funding. There are certainly grounds for confidence. The proportion of Australian youngsters in independent schools has been growing (from around 25% in the 1970s to about 36% today) and the Australian system leverages significant additional funding for the national educational system. With the continuing influence of the Roman Catholic and other churches and the fragmented nature of the Australian political system, it would be a brave government that took the sector on.

The idea that the independent sector is too financially useful to disrupt is of course an argument we have heard in the UK. Budgetary challenges (as in Victoria) can easily combine with political expediency to produce irrational economic outcomes as I reminded our Australian colleagues at the New South Wales AHISA branch meeting at the lovely Abbotsleigh School. Whilst most remain confident, the best schools are planning for the worst and watching events in the UK as closely as their politicians.

An additional challenge for Heads in New South Wales is Section 83C of the NSW Education Act, which states that to be eligible for state funding, independent schools must not operate for profit. Thus far, so good, but the section can be extremely prescriptive in how schools might use their funds beyond those received from the state. This limits schools’ ability to diversify their revenue streams in the way we have seen in the UK. International partnerships or franchises are challenging and governing bodies are almost encouraged to be more parochial and, arguably, more conservative than they might otherwise be. Crucially, it can restrict public benefit activity when not focused on children and young people.

There are exceptions. Engagement with first generation Australians (indigenous peoples) is a major priority for the schools Kate and I visited, as was the place of outdoor learning. From Geelong’s Timbertop to Pymble’s Vision Valley and Scots’ Glengary, high value is placed on students’ experience of adventure and challenge. Kate covers both in her reflections on the trip, so I will write no more save to comment that it does help produce some remarkably well rounded young people.

Phillip Heath, Head at Barker College, with Aboriginal Art (above); and Dr Simon Hyde, Kate Howell and Tom Riley at Pymble Ladies’ College’s Vision Valley; Dr Simon Hyde with students at The King’s School, Parramatta; and Peter Clague (below)

In my almost 4 weeks down under, I visited twenty schools and met some remarkable school leaders, many of whom had experience of working in the UK. It was perhaps fitting that my tour began at St Leonard’s School in Melbourne with Peter Clague, former Head of Bromsgrove, quintessential Kiwi and one of the nicest people around. It ended with HMC’s newest member in Australia, Richard Malpas, now leading his alma mater, Sydney Grammar School. A few days after visiting Anne Johnstone at Ravenswood, she was named Australian School Principal of the year, though I fear this accolade had little connection with our visit. We met members of management teams and bursars, university academics and heads of professional associations as well as students of course. The sun shone (mostly) and as a new visitor to Australia, I discovered a vibrant and exciting country where education is valued by all from immigrant Uber drivers and the hotel concierge to medal-winning Olympians. How I wish I had visited forty years ago!

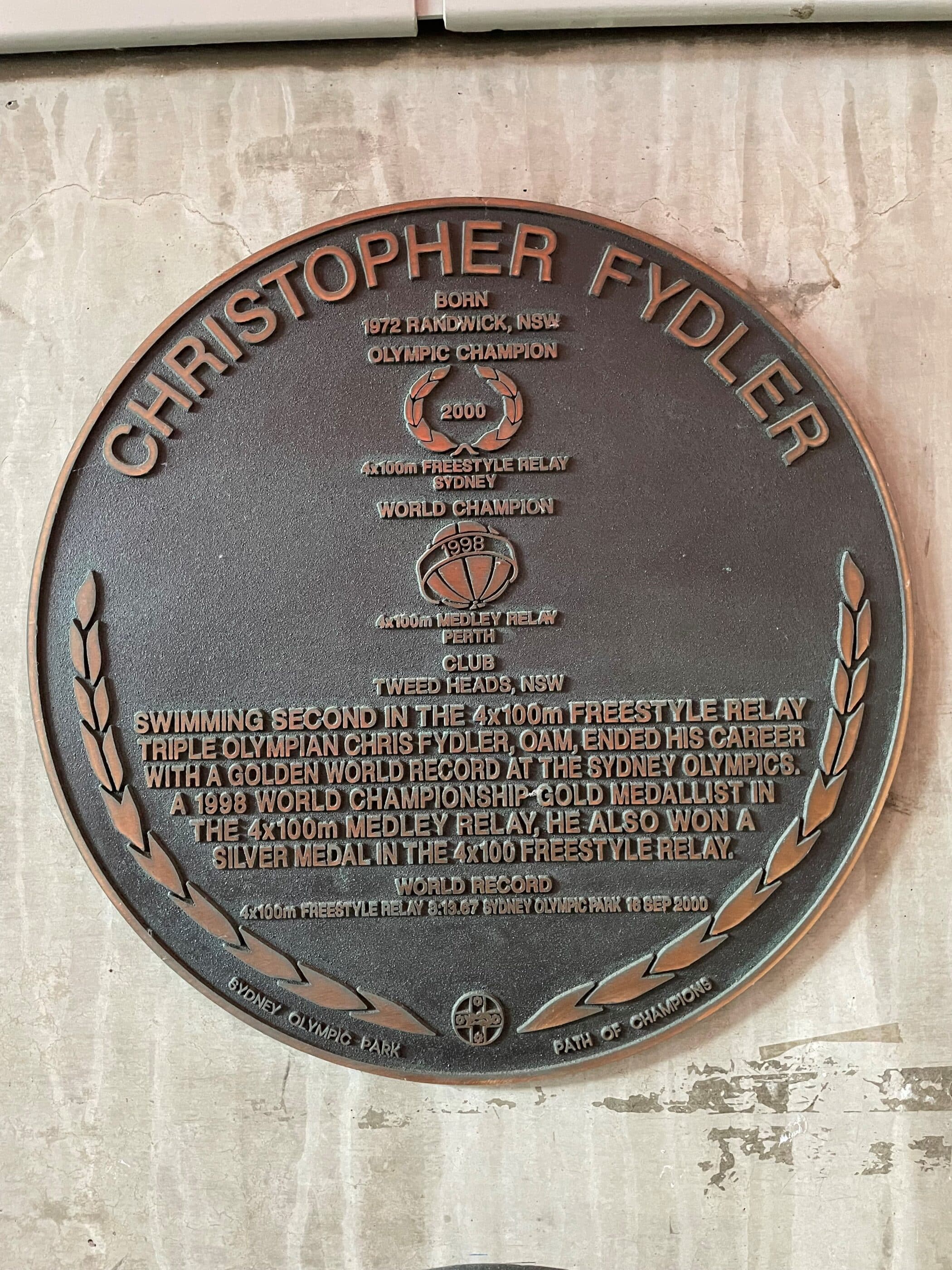

And the title? Well, that reflects the gastronomic bookending of the visit. Aria is one of Sydney’s finest eateries. Situated close to Circular Quay and with stunning views of the Opera House and Harbour Bridge, the restaurant provides the finest of dining in a truly memorable setting. Kate and I are enormously indebted to Chris Fylder (yes, the Olympic Gold Medalist) Chair of Governors and Kate Hadwen, Principal of Pymble Ladies’ College for their generous hospitality. We are delighted to have welcomed them and their world class school into membership of our association. And RSL? The Returned and Services League of Australia struck me as a cross between a working man’s club, branch of the Royal British Legion and a casino. Admittedly the Gosford branch we attended had a remarkable new building, but you can (and we did) get lunch for six people for about the cost of an Aria appetiser. In fairness, my bangers and mash were superb, and we are tremendously grateful to Prof Minkang Kim of the University of Sydney and Derek Sankey for their kind invitation, the chance to talk about their recent book (The Science of Learning and Development in Education) and a fantastic morning’s sailing at Gosford.

Top row (left to right): Olympian Christopher Fydler plaque; Kate Howell; Dr Simon Hyde, Kate Howell, Dr Chris Duncan, Minkang Kim, and Derek Sankey

Middle row (left to right): Sydney Harbour Bridge; inside RSL Gosford; outside RSL Gosford

Bottom row (left to right): Dr Simon Hyde at The Hyde; breakfast at Ravenswood School for Girls; and transport in Sydney